Childhood and youth

Childhood and youth

Alojzije Stepinac is the fifth of eight children born in the family of Josip and Barbara (née Penić). He was born on May 8, 1898, in the village of Brezarići, Krašić parish, situated 50 km from Zagreb. He was baptized the next day as Alojzije Viktor. He completed primary school in Krašić, and as of 1909 attended Gornjogradska classical grammar school and lived at the Archdiocesan orphanage.

After completing the sixth grade, he became a candidate for the priesthood. He graduated ahead of time, on June 28, 1916, and was mobilized to the Austrian army.

After a six-month officer course in Rijeka, he was sent to the Italian front near Gorizia. In the battle of the river Piave, in July 1918, he was captured by the Italians but was released from captivity as a Thessaloniki volunteer in December 1918. In the spring of 1919, he was demobilized.

Ordination to the priesthood

In the autumn of 1919 Stepinac enrolled at the Faculty of Agriculture of the University of Zagreb but soon left to devote himself to farming in his birthplace. At the same time, he became active in Catholic youth groups. For some time he contemplated getting married as this was his father's wish.

In the summer of 1924, he decided to become a priest. In the autumn of the same year, Archbishop Antun Bauer sent him to the Collegium Germanicum et Hungaricum in Rome where he studied at the Pontifical Gregorian University from 1924 to 1931.

He was ordained to the priesthood in Rome on October 26, 1930. He celebrated his First Mass in the Basilica of St. Mary Major and Cardinal Franjo (Francis) Šeper, as his junior colleague and later his successor as the Archbishop of Zagreb and Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, was by his side.

In July 1931 he returned to his homeland after completing a double major in philosophy and theology. In the then Yugoslavia the dictatorial regime was in power and the government was trying to weaken the influence of the Catholic Church.

At the archbishop's palace Stepinac was the master of the ceremonies. For a short period, he was the manager in charge of settling disputes between the priests and their parishioners in several parishes. In his free time, he devoted himself to charitable work and Archbishop Bauer founded the archdiocesan Caritas at his initiative on November 23, 1931.

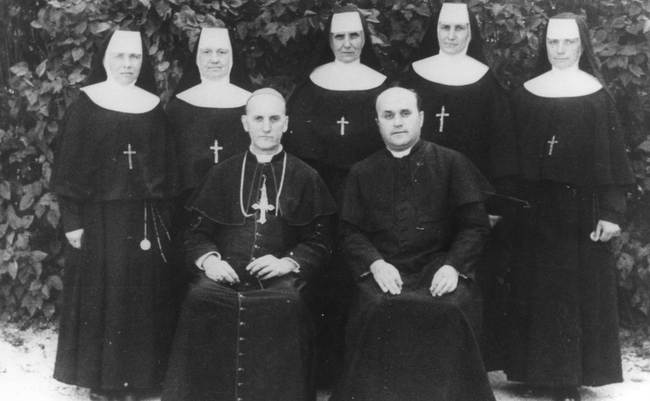

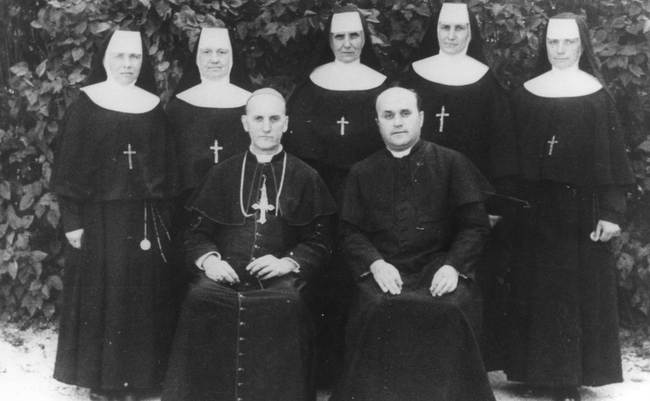

The youngest bishop

Pope Pius XI appointed him coadjutor archbishop with the right of succession to the episcopal see on May 28, 1934. At the age of 36 and almost four years of priesthood he was the youngest bishop in the world. On Midsummer's Day, June 24, 1934, he was ordained as bishop in the Zagreb cathedral. The archbishop included him in the most intensive pastoral of the large archdiocese.

Upon the death of Archbishop of Zagreb Antun Bauer on December 7 he became the Archbishop of Zagreb and president of the then Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia. As the shepherd of the Church of Zagreb, he tried to be in touch with the clergy and the faithful of the entire archdiocese. He promoted overall spiritual renewal, especially devotions to the Eucharist and to St. Mary, Mother of God. He strongly cared for the pastoral care of the family and youth and the active participation of laity in the Catholic action.

He advocated for good Catholic press (he started publishing the Catholic journal Hrvatski Glas [The Croatian Voice]). He encouraged the publishing of the new integral translation of the Holy Scripture. He founded many new parishes, 14 of them in Zagreb.

He included almost all religious orders and societies in pastoral care. He founded the first Croatian Karmel in Brezovica. Also, he and all Croatian bishops intensely planned on celebrating the 1300th anniversary of their relationship with the Holy See (641 - 1941), which was postponed until the celebration in Marija Bistrica in 1984 due to war.

Turmoil of war

Turmoil of war

During World War II, after the German occupation of Yugoslavia, the Independent State of Croatia was established as a puppet state of the Axis Powers. Stepinac did not attach himself to any of the political parties or movements. Consistent in his patriotism and above all true to his mission of a shepherd, he unreservedly, fearlessly, and publicly condemned racial, ideological, and political persecutions. In his public appearances and written addresses, he courageously demanded respect for every person regardless of their race, nationality, faith, gender, and age.

True to the Gospel, he relentlessly condemned crimes against humanity and all other injustices. After the racial laws were passed in April 1941, he submitted a fierce protest note to the government. He rescued persecuted Jews, Serbs, Romani people (Gypsies), Slovenians, Poles and Communist Croats.

In the first months of the Independent State of Croatia, he intervened and said: ‘Christian morale does not allow us to kill the hostage for the crimes committed by others’. On October 25, 1942, in the Zagreb cathedral, he stated: ‘Every nation and every race living on Earth has the right to a decent living and to be treated as humans.

No matter which race they belong to, Gypsy race or any other, whether they are African-Americans or sophisticated Europeans, detested Jews or arrogant Aryans, they have the right to pray without any difference: ‘Our Father, Who art in heaven!’ And if God gave everyone that right, how can a human authority deny them that right.’ He opposed violent conversions and when he could not prevent them, he instructed the clergy in secrecy that those who wished to convert to Catholicism to save their lives were to be accepted in the Catholic Church with no strings attached, because ‘when this time of madness and savagery is over, those who convert for their religious beliefs will remain Catholics and others will return to theirs.’

The poor and the persecuted sought refuge in him. He provided shelter for some 300 priests exiled from Slovenia. His Caritas helped not only the Croats that were in danger but everybody: Serbs, Jews, Slovenians, Poles, etc. Because of this, and especially because he condemned Fascist and Nazi persecutions, Stepinac became their enemy. Hitler’s Gestapo had a plan to kill him and the then government demanded from the Holy See on several occasions for Stepinac to be removed from the Archdiocesan See in Zagreb.

Communist attacks

Communist attacks

After World War II in Croatia and the entire Yugoslavia, the Communist party, imbued with Bolshevik ideology and especially militant atheism, came to power. By May 17, 1945, Archbishop Stepinac was arrested, and by June 3 in prison. The next day, on June 4, Tito wanted to talk to him. From that conversation, just like the one Tito had with the representatives of the Catholic clergy in Zagreb two days earlier, it was evident that the new regime wanted a ‘national Church’, independent of the Holy See. For Stepinac, that meant interfering with Catholic unity. Soon it became obvious that it was a planned and violent persecution of the Church aimed not only at bishops and priests but the faithful as well.

An unbelievable media campaign against the Church and especially Archbishop Stepinac flared up quickly. The campaign of varying intensity lasted until the historical descent of Communism from the political scene.

In September 1945 Stepinac convoked the Bishops’ Conference to look into the new circumstances. On September 22 the bishops published a letter which boldly documents all the violence and injustice of the new government against faith and the Church as well as against the freedom of conscience of their citizens during the war and post-war period.

An even fiercer attack followed, focusing especially on Stepinac, the Archbishop of Zagreb. It began with assaults like the stoning in Zaprešić on November 4, 1945. After that, the archbishop was forced to stay indoors. In January 1946 the government asked the Holy See via the new Apostolic Prelate

Hurley to remove Stepinac from the archdiocesan see.

Rigged trial

He was arrested for the second time on September 18, 1946, after a series of violent abuses and assaults against him, and on September 30 he was prosecuted in a rigged trial. His famous speech of October 3, 1946, was not just his defense but an indictment of an unfair trial and a profession of faith he was willing to die for.

Based on extorted depositions and false testimonies, even forged documents, on October 11, 1946, Stepinac was, despite being innocent, sentenced to 16 years in prison and hard labor as well as to five years’ house arrest.

On October 19, 1946, he was sent to a maximum security prison in Lepoglava where he served his sentence until December 5, 1951. He was allowed to celebrate Mass and read theological books but was held in strict isolation and subjected to consistent humiliation and stress. It seems he was being poisoned as well, which greatly influenced his health. According to witnesses in the process of his beatification, he was on the list of prisoners sentenced to death.

On December 5, 1951, after 1864 days spent in the Lepoglava prison, Stepinac was relocated to serve his sentence in house arrest in Krašić, his birthplace. On January 12, 1953, while being in captivity, Pope Pius XII appointed him cardinal.

As a result, the then-government broke off diplomatic relations with the Holy See. He could not go to Rome to be officially appointed cardinal nor attend conclaves upon the death of Pius XI, as he was not sure whether he would be able to return to his homeland. He wished to remain with his people no matter the cost.

Imprisonment and death

Imprisonment and death

While being imprisoned and in strict isolation he devoted himself to the apostolate of writing. He wrote thousands of sermons and various spiritual compositions. He sent more than 5000 letters, of which 700 are preserved, to many bishops, priests, and laymen. In his letters, as a man of avid faith and unyielding hope completely devoted to God, he encouraged, comforted, and inspired them to endure in faith and church unity. These letters, just like his behavior during the trial and imprisonment, reveal sincere affection even for those who persecuted and wrongfully accused him.

All his statements, letters, and even his three wills revolve around the prayer for his enemies and forgiveness.

In the spring of 1953, and already in Lepoglava, he started to suffer from polycythemia rubra vera, vein thrombosis, and bronchial catarrh. He needed constant medical care and doctors did everything in their power to help despite him being under strict supervision of the regime. Stepinac refused special treatment which could mean that he yielded before unfair judges and the regime thus shaking the faith of the clergy and laity. So the growing pains became part of his life in imprisonment and he endured them until his death.

Stepinac died a holy death on February 10, 1960, while serving his unjust prison sentence, in ex aerumnis carceris or, as the martyr vocabulary defines it, a toll of imprisonment, praying for his persecutors and Lord’s words on his lips: ‘Father Thy Will Be Done!’

The Christ faithful recognized and honored his virtuous life and death of a martyr, especially after his death, despite Communist prohibitions and persecutions.

Pope John Paul II beatified him on October 3, 1998, in Marija Bistrica. Stepinac was buried in the tomb of Zagreb’s archbishops behind the main altar of the Zagreb Cathedral. Flowers and candles as well as thank-you notes from people whose prayers were answered by the intercession of Blessed Aloysius Stepinac decorate that wonderful space as the pilgrims recognized him as a personal advocate and an advocate of the Croatian people.